Good morning! Welcome to The Daily Grind for Monday, August 4.

Today we are looking at a piece from Noah Smith about the AI datacenter boom—are we headed for a financial crash?

For context, our One Page transports us back 100 years to understand the last great infrastructure boom, led by John D. Rockefeller and company.

Finally, we’ll use our One Question to adopt a mindset of gratitude.

Let’s get into it:

📰 One Headline: Are AI Data Centers Fueling the Next Financial Crisis?

Over the weekend, economist and Substacker Noah Smith contemplated whether the current AI data center boom could lead to a financial crisis — and if so, what kind?

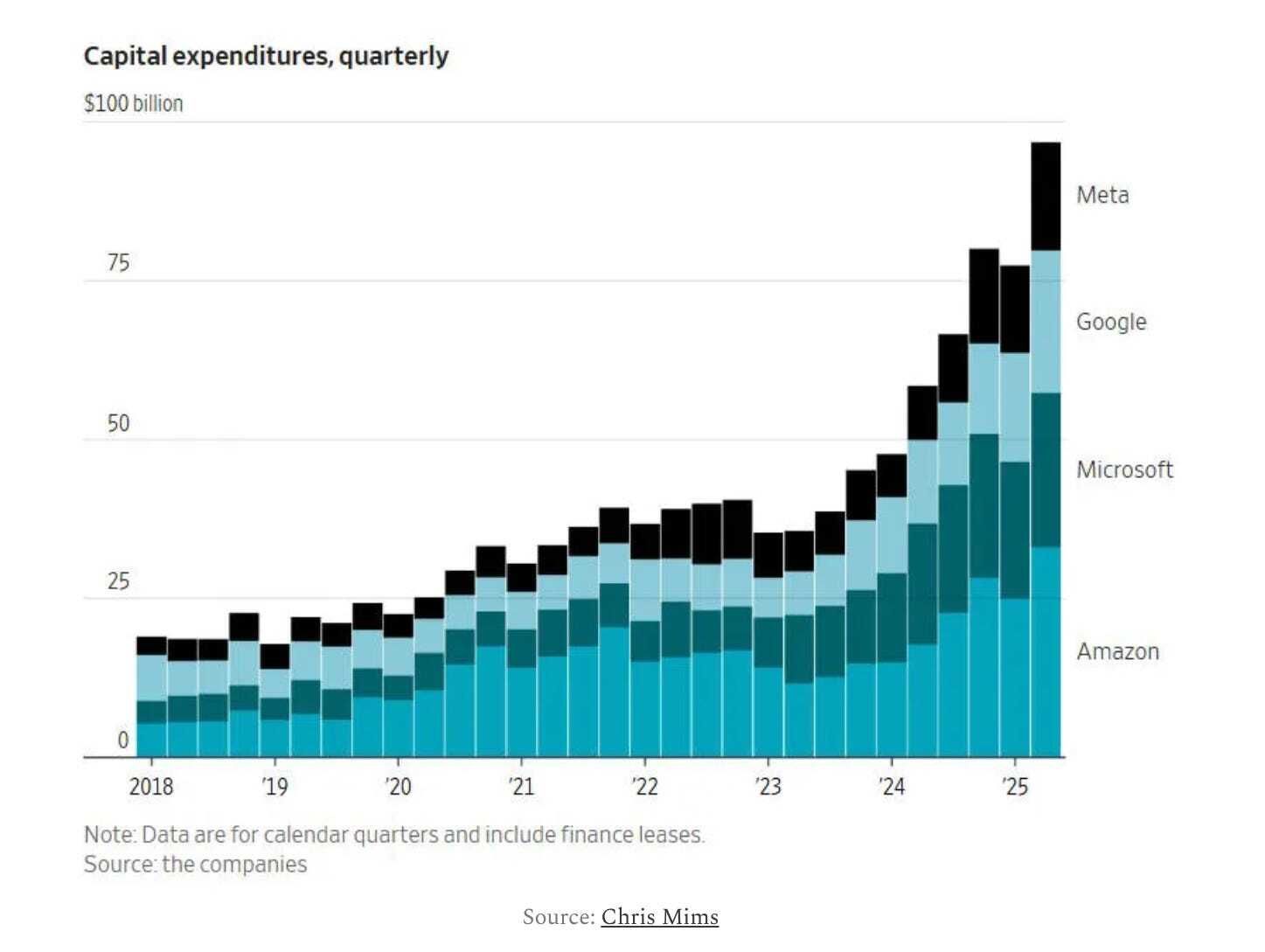

It’s easy to look at the current capital expenditures (CapEx) of large tech companies today and say, “Yep, that’s a bubble.” The numbers are jaw-dropping and echo past boom-bust cycles.

The CapEx on data centers has already exceeded—or at worst, matched—the amount spent on telecoms infrastructure during the Dot-Com and Web 2.0 era.

(Note: Smith points out that the chart above shows the CapEx for telecom in 2020, long after the Dot-Com bust. In 2000, Smith shared, the telecom CapEx peaked at 1.2% of GDP, on par with AI datacenters today, though data center build-out seems far from peaking.)

This level of spending has also quite literally propped up the economy this year. According to Christopher Mims in the Wall Street Journal:

Capex spending for AI contributed more to growth in the U.S. economy in the past two quarters than all of consumer spending, says Neil Dutta, head of economic research at Renaissance Macro Research, citing data from the Bureau of Economic Analysis.

But even if you believe every bubble is bound to burst, the nature of the bubble is crucial, according to Smith.

First, who is funding the bubble? During the Dot-Com bubble, for example, technology companies were primarily funded by bonds, venture capital, and public markets. Importantly, the banking system had little exposure to the technology industry at the time.

“When a financial bubble and crash is mostly a fall in the value of stocks and bonds, everyone takes losses and then just sort of walks away, a bit poorer — like in 2000,” said Smith.

This is different than the 2008 housing crisis, where banks supplied much of the capital that went into sub-prime mortgages. When defaults happened, the banking system was hit hard.

In today’s AI data center boom, most of the capital has come from private companies, bonds, and venture capital—so far.

But as Smith and others point out, more and more data centers are being funded by a service called private credit. Private credit is the debt-focused cousin of private equity. They lend out money for large, capital intensive projects. Private capital has exploded in the last few years, and it seems like banks are big funders.

According to Smith:

Private credit funds take some of their financing as equity, but they also borrow money. Some of this money is borrowed from banks. In 2013, only 1% of U.S. banks’ total loans to non-bank financial institutions was to private equity and private credit firms; today, it’s 14%.

This could be a sign that if the AI bubble bursts, banks could be on the hook.

Smith summarizes his concerns about the AI data center boom, saying the seeds are sewn for a 2008-style financial crisis:

[W]hen I look at this entire landscape, it seems to me that some of the basic conditions of a financial crisis are at least starting to fall into place:

But what will ultimately cause the bubble to burst is whether or not big tech companies land this AI plane. There is no guarantee that generative AI will continue to improve at the pace it has over the last three years—but that might not even matter given the productivity gains it has already provided.

On the other hand, significant improvements to the efficiency of AI chips—such as those being developed by Positron—could turn data center supply into a glut overnight.

The best piece of news in this story is just how much big tech companies are betting their own money on the AI wave. The more private money spent vs. bank loans (or private credit loans), the better for the rest of us in the bubble bursts.

It will be important to watch the size of Private Capital over the next year—does it continue to grow as a percentage of total debt? And do banks continue to fund it?

If so, we can expect that if (or when?) the bubble bursts, it’s going to hurt.

🔗 A Few Good Links

APM Reports: What’s Wrong with How Schools Teach Reading

📚 One Page: Titan by Ron Chernow

Today’s AI data center boom is drawing many comparisons to the age of robber barons, when railroad, oil, and industrial infrastructure CapEx reached 6% of total GDP.

John D. Rockefeller is the face of the era, though he was only just starting out during the crash of 1873 (when banks funded and oversupplied railroad infrastructure). From that moment on—for the next 50 years—Rockefeller’s Standard Oil dominated public and private life.

Titan by Ron Chernow is the definitive biography on Rockefeller and helps us understand the logic of Rockefeller and the other industrial titans. Monopoly, in Rockefeller’s eyes, was the only way to tame the wild oil industry:

From the three-year interview he gave privately to William O. Inglis in the late 1910s, it is clear that Rockefeller brooded for many years on a theoretical defense of monopoly. His comments are fragmentary and do not cohere into a full-blown system, yet they show that he gave the subject a great deal of intelligent thought, much more than one might have expected. He knew that he had latched on to a mighty new principle, and arose as the prophet of a new dispensation in economic history. As he said, “It was the battle of the new idea of cooperation against competition, and perhaps in no department of business was there a greater necessity for this cooperation than in the oil business.”

Rockefeller’s logic deserves some scrutiny. If, as he asserted, Standard Oil was the efficient, low-cost producer in Cleveland, why didn’t he just sit back and wait for competitors to go bankrupt? Why did he resort to the tremendous expense of taking over rivals and dismembering their refineries to slash capacity? According to the standard textbook models of competition, as oil prices fell below production costs, refiners should have retrenched and padlocked plants. But the oil market didn’t correct itself in this manner because refiners carried heavy bank debt and other fixed costs, and they discovered that, by operating at a loss, they could still service some debt. Obviously, they couldn’t lose money indefinitely, but as they soldiered on to postpone bankruptcy, their output dragged oil prices down to unprofitable levels for everybody.

Hence, a perverse effect of the invisible hand: Each refiner, pursuing his own self-interest, generated collective misery. As Rockefeller phrased it, “Every man assumed to struggle hard to get all of the business … even though in so doing he brought to himself and the competitors in the business nothing but disaster.”

In a day of primitive accounting systems, many refiners had only the haziest notion of their profitability or lack thereof. As Rockefeller noted, “oftentimes the most difficult competition comes, not from the strong, the intelligent, the conservative competitor, but from the man who is holding on by the eyelids and is ignorant of his costs, and anyway he’s got to keep running or bust!”

Are today’s tech titans following the same logic? And if this analogy holds, who are the companies “holding on by the eyelids?”

❓ One Question: What are you grateful for today?

An AI-driven financial crisis is out of our hands (unless you’re Zuck. Hi Zuck). While it’s useful to think and plan ahead, dwelling on it will just make us miserable and unproductive.

Let’s focus on what we can control, and it helps when we can shift our mindset into one of gratitude.

Before planning out your week, ask yourself: “What am I grateful for today?”

Start a list, write it down. Dwell on those things you are grateful for, and feel some of the anxiety wash away. Your weekly planning will be more productive—and positive—if you start with this grateful mindset.

🗳️ Wrap Up and Feedback:

That’s it for today’s Daily Grind! Thank you to everyone who has followed along over this first month. I’m eager to keep this going, but would love your feedback.

Instead of a poll, I have a question for you:

Do you follow this newsletter on Substack, via Email, or through Social Media?

I ask because I’m considering a move from Substack to Beehiiv, where I can have more control over the design and outreach experience. But I don’t want to alienate a large group of Substack readers! Let me know.

Talk to you tomorrow.

Cheers,

Benn