Good morning!

Welcome to The Daily Grind for Wednesday, July 16.

Today we are getting an inside look at OpenAI, one of the fastest growing and most consequential startups in history.

Then we’ll compare OpenAI culture to another legendary startup: PayPal.

Finally, we’ll wrap with some reflection on finding joy in whatever experience you’re going through today.

First: If you’ve read every Daily Grind so far this week, can you do me a favor? Send me an comment and tell me what you’ve enjoyed most. I’d love to know!

And if you’re feeling generous, share with a friend:

📰 One Startup Headline: What life inside OpenAI is really like

Yesterday, a former OpenAI employee wrote a long and fascinating blog post detailing life inside the AI behemoth.

Calvin French-Owen recently left OpenAI after roughly a year, where he mainly worked on Codex, the startup’s new AI code editor. French-Owen shared a long list of reflections on the company’s culture and technology.

“To put it up-front: there wasn't any personal drama in my decision to leave–in fact I was deeply conflicted about it,” said French-Owen to open his post. “It's hard to go from being a founder of your own thing to an employee at a 3,000-person organization. Right now I'm craving a fresh start.”

To be fair, French-Owen was more than a rank-and-file employee. Before joining OpenAI, he was the founder and CEO of Segment, which was acquired by Twilio for a reported $3.2 billion in 2020.

The context is important, I think, because it shows he didn’t have to be at OpenAI and put up with the stress. But he did, and from his reflections, he gained a lot from the experience.

Here are some of the more interesting reflections on the company, but I recommend you read the full post when you have a chance.

The first thing to know about OpenAI is how quickly it's grown. When I joined, the company was a little over 1,000 people. One year later, it is over 3,000 and I was in the top 30% by tenure. Nearly everyone in leadership is doing a drastically different job than they were ~2-3 years ago.

Of course, everything breaks when you scale that quickly: how to communicate as a company, the reporting structures, how to ship product, how to manage and organize people, the hiring processes, etc.

There's a strong bias to action (you can just do things). It wasn't unusual for similar teams but unrelated teams to converge on various ideas. I started out working on a parallel (but internal) effort similar to ChatGPT Connectors. There must've been ~3-4 different Codex prototypes floating around before we decided to push for a launch. These efforts are usually taken by a small handful of individuals without asking permission. Teams tend to quickly form around them as they show promise.

OpenAI changes direction on a dime. This was a thing we valued a lot at Segment–it's much better to do the right thing as you get new information, vs decide to stay the course just because you had a plan. It's remarkable that a company as large as OpenAI still maintains this ethos–Google clearly doesn't. The company makes decisions quickly, and when deciding to pursue a direction, goes all in.

There is a ton of scrutiny on the company. Coming from a b2b enterprise background, this was a bit of a shock to me…

As a result, OpenAI is a very secretive place. I couldn't tell anyone what I was working on in detail. There's a handful of slack workspaces with various permissions. Revenue and burn numbers are more closely guarded.

As often as OpenAI is maligned in the press, everyone I met there is actually trying to do the right thing. Given the consumer focus, it is the most visible of the big labs, and consequently there's a lot of slander for it.

Nearly everything is a rounding error compared to GPU cost. To give you a sense: a niche feature that was built as part of the Codex product had the same GPU cost footprint as our entire Segment infrastructure (not the same scale as ChatGPT but saw a decent portion of internet traffic).

The thing that I appreciate most is that the company is that it "walks the walk" in terms of distributing the benefits of AI. Cutting edge models aren't reserved for some enterprise-grade tier with an annual agreement. Anybody in the world can jump onto ChatGPT and get an answer, even if they aren't logged in. There's an API you can sign up and use–and most of the models (even if SOTA or proprietary) tend to quickly make it into the API for startups to use. You could imagine an alternate regime that operates very differently from the one we're in today. OpenAI deserves a ton of credit for this, and it's still core to the DNA of the company.

Safety is actually more of a thing than you might guess if you read a lot from Zvi or Lesswrong. There's a large number of people working to develop safety systems. Given the nature of OpenAI, I saw more focus on practical risks (hate speech, abuse, manipulating political biases, crafting bio-weapons, self-harm, prompt injection) than theoretical ones (intelligence explosion, power-seeking).

The company pays a lot of attention to twitter. If you tweet something related to OpenAI that goes viral, chances are good someone will read about it and consider it. A friend of mine joked, "this company runs on twitter vibes". As a consumer company, perhaps that's not so wrong. There's certainly still a lot of analytics around usage, user growth, and retention–but the vibes are equally as important.

The Codex sprint was probably the hardest I've worked in nearly a decade. Most nights were up until 11 or midnight. Waking up to a newborn at 5:30 every morning. Heading to the office again at 7a. Working most weekends. We all pushed hard as a team, because every week counted. It reminded me of being back at YC.

It's hard to overstate how incredible this level of pace was.

Say what you will, OpenAI still has that launching spirit.

OpenAI is perhaps the most frighteningly ambitious org I've ever seen. You might think that having one of the top consumer apps on the planet might be enough, but there's a desire to compete across dozens of arenas: the API product, deep research, hardware, coding agents, image generation, and a handful of others which haven't been announced. It's a fertile ground for taking ideas and running with them.

This post, intentionally or not, coincides with Karen Hao’s Empire of AI, as it makes its rounds in tech reading circles. Hao’s book documents the imperialist nature (I.e., frighteningly ambitious?) of OpenAI and the implications for the rest of us.

It is on my list to read and will report back. Shout out to Danny Goodman for the recommendation.

🔗 A Few Good Links

Here are a few more stories to explore:

OSTechnix: Linux Reaches 5% Desktop Market Share In USA

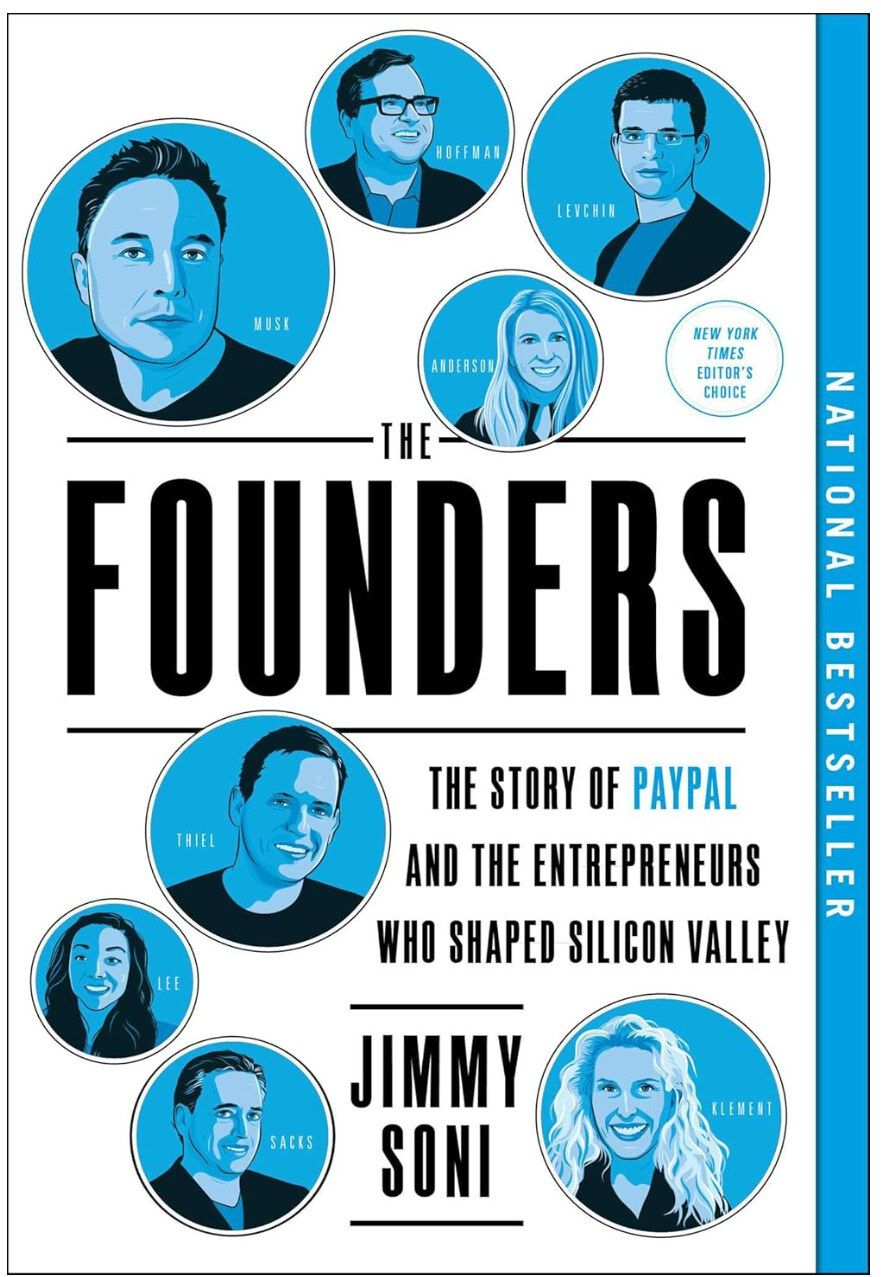

📚 One Page: The Founders by Jimmy Soni

Reading about OpenAI’s fast-paced, hyperscale startup culture reminded me of stories from PayPal’s early days.

The best account is from Jimmy Soni and his book, The Founders: The Story of PayPal and the Entrepreneurs Who Shaped Silicon Valley.

Speed had a cost—but one the company was willing to cover. Designer Ryan Donahue remembered that he once broke a key site function on a Friday afternoon, during a moment of heavy payment volume. He alerted the company’s CTO, Levchin, who went off and diagnosed the issue.

“He came back… and he’s like, ‘Congratulations. You single-handedly broke the ability to send money and cost the company $1.5 million.’” Donahue panicked. “I’ve never made such an expensive mistake before,” he said. “It was okay. He was laughing about it. And I was like, ‘This place is awesome.’”

Musk and other senior leaders tolerated failures as a side effect of iteration. “I remember once Elon saying one thing which was like, ‘If you can’t tell me the four ways you fucked something up… before you got it right, you probably weren’t the person who worked on it,’” Giacomo DiGrigoli recalled.

Musk echoed this sentiment. “If there were two paths where we had to choose one thing or the other, and one wasn’t obviously better than the other,” he explained in a 2003 public talk at Stanford, “then rather than spend a lot of time trying to figure out which one was slightly better, we would just pick one and do it. And sometimes we’d be wrong…. But oftentimes it’s better to just pick a path and do it rather than just vacillate endlessly on the choice.”

The Founders is worth a read for anyone interested in startup life. Get the book.

❓ One Question: What will you miss most about this time in your life?

I can imagine that as Calvin French-Owen pulled all-nighters to launch Codex—with a newborn at home, no less—he felt pretty miserable. But in hindsight, as he recalls, “It's unquestionably one of the highlights of my career.”

Which leads to a wonderful question:

What will you miss most about this time in your life?

No matter what you are going through, there are moments worth appreciating.

When my wife’s mother passed away two years ago, we had a surprising number of joyful moments with her family. I hold those memories dear.

What little moments of joy will you miss about this time in your life?

🗳️ Wrap Up and Feedback:

That’s it for today’s Daily Grind! Would love your feedback:

If you found today’s post interesting, please share with a friend:

See you tomorrow!

Cheers,

Ben